The Lost World

By the late afternoon most had forgotten I was there and, having left their weapons on the ground and taking huge gulps of the homemade beer, were now rather drunk. These men of the village were sitting in a clearing talking, passing around calabashes full to the brim with sorghum beer. A few were building a hut from large branches, a detail machete-ing the limbs and another constructing the roof and walls. The weather was pleasant and the sound of laughter hung in the air. If it had not already been proven to me I would not have believed that these Surma villagers were hardened killers, a product of constant inter-tribal raiding.

I had come to the Omo River, in south-west Ethiopia near the Sudanese border, to explore the west side of the valley. It is one of the last corners of Africa that is almost untouched by the outside world, where tribes continue a life unchanged for centuries, even millennia. The eastern bank of the lower Omo is often visited by tourists in many guises. Some are photographers, others are merely curious: voyeurs to a culture so tribal and alien they must taste it. It can be accessed by Land Cruiser and there are dirt tracks, that bring the tribes T-shirts, spaghetti and disease. Across the river, however, over which there is no bridge, lurks a more vivid and dangerous world rarely visited by the outside: western Omo.

I had come to the Omo River, in south-west Ethiopia near the Sudanese border, to explore the west side of the valley. It is one of the last corners of Africa that is almost untouched by the outside world, where tribes continue a life unchanged for centuries, even millennia. The eastern bank of the lower Omo is often visited by tourists in many guises. Some are photographers, others are merely curious: voyeurs to a culture so tribal and alien they must taste it. It can be accessed by Land Cruiser and there are dirt tracks, that bring the tribes T-shirts, spaghetti and disease. Across the river, however, over which there is no bridge, lurks a more vivid and dangerous world rarely visited by the outside: western Omo.

I had arrived in the western Surma lands from the lands of the Bench people, approaching the Omo River Valley from the north west. I had walked the bush from Dima westwards, desperate to get deeper and deeper into this tribal land, where roads and cars are almost unheard of. I had planned to take a donkey to help with carrying stores, but Tsetse flies were common this time of year and there were no donkeys to be found.

I had arrived in the western Surma lands from the lands of the Bench people, approaching the Omo River Valley from the north west. I had walked the bush from Dima westwards, desperate to get deeper and deeper into this tribal land, where roads and cars are almost unheard of. I had planned to take a donkey to help with carrying stores, but Tsetse flies were common this time of year and there were no donkeys to be found.

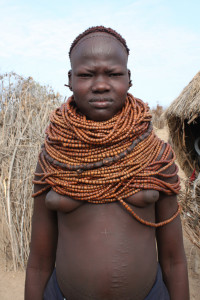

The Surma are an aggressive warrior tribe consisting of many clans. The women wear lip plates, some reaching eight inches in diameter. The men go naked, sometimes with a blanket slung over the shoulder and carry a spear or rifle. During my time in the Surma country I was lucky enough to see a donga fight, where men prove themselves in single combat with eight foot donga sticks. Deep in the bush eight hundred men gathered in a clearing where men from different villages entered the arena with war dancing and chanting. The drinking and fighting began, a spectacle of awful colour and savagery. Fights only end to prevent a final death-blow. Faces ran with blood, victors were carried into the bush and paraded back in on the shoulders of their comrades, horns sounded and warriors screamed and bayed. Shots were fired in the air to rally each group and celebrate the victors., one time sending a bullet fizzing past my ear. After staying a few hours, I snuck off into the bush with my interpreter: aggression of a donga fight soon spills over and I was not surprised to hear that village feuds had flared up. Several men had been shot, bringing the fight to an end.

Taking two Surma scouts, we spent the next two days climbing the hills, machete-ing our way through the dense bush, to reach the hill-top villages of the Dizi tribe. I spent time with these peaceful people nestled on a ridge amongst false banana trees to replenish stores and select men for my journey south. The Dizi people had been pushed out of their ancestral lands in the north by the Surma and their last bastion of existence was in the relative safety of the hilltops. When we had assembled a party we headed south, through their Surma enemy’s land towards the Nyangatom tribes, whom they call the Bume.

We were all armed with a motley collection of old Mosin Nagant bolt actions, Kalashnikovs and non-descript French semi-automatics. One of our party insisted on taking a grenade (stolen from the army many years before), which he hung from his belt by the safety pin. Being a slow walker, I let him walk quite a way behind me. On the way confrontations with the Surma were frosty and tense. One night we shared our camp with a pride of lion that groaned and grunted most of the night, but kept away by our fire. To the south, the Nyangatom were fighting a bitter battle with their bitter enemies, the Turkana. Needless to say, the Dizi left me and I pushed on the last few days without them.

We were all armed with a motley collection of old Mosin Nagant bolt actions, Kalashnikovs and non-descript French semi-automatics. One of our party insisted on taking a grenade (stolen from the army many years before), which he hung from his belt by the safety pin. Being a slow walker, I let him walk quite a way behind me. On the way confrontations with the Surma were frosty and tense. One night we shared our camp with a pride of lion that groaned and grunted most of the night, but kept away by our fire. To the south, the Nyangatom were fighting a bitter battle with their bitter enemies, the Turkana. Needless to say, the Dizi left me and I pushed on the last few days without them.

My time with the Nyangatom was short but eventful. The tribe was wracked with frequent raids from the neighbouring Turkana, who would often make off with goats and cows. While I was there a goats-boy was stabbed in the stomach, his head cut off and mutilated and the goats taken. That evening under the largest tree in the area, the Nyangatom villagers rallied. It was decided that they would in turn raid the Turkana. In the subsequent raid my host narrowly escaped death, receiving only a bullet in his arm.

I found the Nyangatom nice people and I liked the look of them. I found them to be full of contradictions: they would eat a whole cow one day, and starve the next. Once I killed a crocodile that had fallen into one of their wells and cooked it for them. They would not try the meat, the most hardened warriors disappearing when it was time to eat it. Needless to say, the children of the village wolfed it down. The crocodile and the hippo are truly feared, even when dead it seemed. I had heard that the villages near the river had only discovered fish five years earlier, since no-one would approach the water lest they be attacked by a hippo.

I found the Nyangatom nice people and I liked the look of them. I found them to be full of contradictions: they would eat a whole cow one day, and starve the next. Once I killed a crocodile that had fallen into one of their wells and cooked it for them. They would not try the meat, the most hardened warriors disappearing when it was time to eat it. Needless to say, the children of the village wolfed it down. The crocodile and the hippo are truly feared, even when dead it seemed. I had heard that the villages near the river had only discovered fish five years earlier, since no-one would approach the water lest they be attacked by a hippo.

Upon my return I crossed the Omo River in a small craft, at a point where the river moved too fast for hippo, though there were plenty of crocodiles. Getting down to the river was a feat in itself, as the earth fell away to make a cliff some ten meters high. Upon reaching the other side I soon found a Land Cruiser of a photographer of a well-known geographical magazine. I sat on the roof as we scrambled over the dirt road through the lands of the friendly Hamer people. “You wanna Coke?” he drawled before stopping to photograph passing Hamer tribesmen from the window of the vehicle. On this side of the river, although still remote, I saw tribesmen in T-shirts, whilst some begged me for plastic water bottles I did not have and I wondered how long it would take for this to reach the people whose world I had just left.

Watch video of the donga fight.

Read more about Omo expedition.