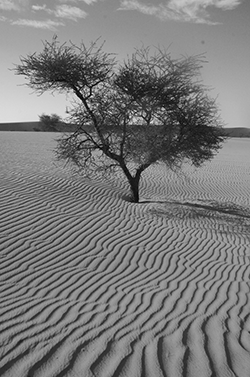

Saharan Crossing 2008

In 2008 I set out to cross the Sahara travelling as one of the Touareg nomads who live there and to experience their threatened lifestyle first hand. Armed with a sword and some schoolboy French I became the first westerner in living memory to cross the Tanezrouft area of the Sahara in Algeria by camel. I rode over a thousand miles through the desert, having to dodge bandits, suffer thirst and hunger and guide my caravan through the civil war in Mali.

Ahmed whispered for me and Ouankilla to join him on the ridge of the sand dune that sheltered our encampment from the tearing Saharan wind. With our headcloths wrapped tightly around our faces to keep out the stinging sand, we peered into the darkness. Behind us, young Aziz tended the fire, cutting up the remains of the goat we had slaughtered a few days earlier with his dagger. In front of me the swirling desert looked bleak and unforgiving, but Ahmed was convinced that he had seen a light. We were deep in the Tanezrouft, an area of the Sahara the size of Germany, whom the Touareg call The Land of Terror. It is a barren and desolate place that lacks landmarks, water and vegetation: a desert within a desert. The light Ahmed had seen was troubling, as it meant there were others out there in the storm. The nomads are a sociable people who often ride out of their way to exchange greetings with other desert folk, but out here such meetings took a more sinister turn. This area was known for its banditry, and being four of us with two antiquated rifles and five camels we presented an easy target. We lay still for what seemed like an eternity straining our eyes into the gloom. There was indeed a light, a tiny pin prick of a flame some distance from us. We decided to put out our own fire and to couch our camels near us just in case.

Ahmed whispered for me and Ouankilla to join him on the ridge of the sand dune that sheltered our encampment from the tearing Saharan wind. With our headcloths wrapped tightly around our faces to keep out the stinging sand, we peered into the darkness. Behind us, young Aziz tended the fire, cutting up the remains of the goat we had slaughtered a few days earlier with his dagger. In front of me the swirling desert looked bleak and unforgiving, but Ahmed was convinced that he had seen a light. We were deep in the Tanezrouft, an area of the Sahara the size of Germany, whom the Touareg call The Land of Terror. It is a barren and desolate place that lacks landmarks, water and vegetation: a desert within a desert. The light Ahmed had seen was troubling, as it meant there were others out there in the storm. The nomads are a sociable people who often ride out of their way to exchange greetings with other desert folk, but out here such meetings took a more sinister turn. This area was known for its banditry, and being four of us with two antiquated rifles and five camels we presented an easy target. We lay still for what seemed like an eternity straining our eyes into the gloom. There was indeed a light, a tiny pin prick of a flame some distance from us. We decided to put out our own fire and to couch our camels near us just in case.

I had come to the Sahara to witness the Touareg way of life that has remained almost completely unchanged since man first settled in the desolate wastes of the desert. I wanted to experience their threatened lifestyle first hand, one that is disappearing fast in the wake of aggressive policies pursued by North African governments and the encroaching tourist industry.

In London I had become increasingly frustrated by a dreary life painted in bland tones by concrete buildings and the choking fumes of traffic. I wished to undertake desert travel with the nomads, I wanted to taste the harshness of the desert and derive an understanding of the uncompromisingly gruelling life they led and the freedom of the wilderness. My goal was to reach Timbuktu, crossing from Algeria and approaching it from the north-east.

I had bought five camels in the camel market in Tamanrasset, southern Algeria, with the help of a kindly Touareg. It was in Tamanrasset that I had persuaded the Touareg who live in the surrounding Hoggar mountains to take me across the Tanezrouft to Mali. Indeed, I had been lucky as I was able to track down the only man alive in this part of the country who knew the route. His name was Ouankilla but the tribesmen referred to him as amara, meaning wise-man in Tamasheq, the language of the Touareg. I had arrived in the country knowing little of how to go about my plans of travelling with these people. However, upon my arrival I was quickly taken in by a Touareg woman in Djanet, near the Libyan border. She knew of Touareg who knew tribesmen who in turn knew further people who could take me. I did not speak their language, but one of the Touareg spoke passable French with whom I could talk. Over the course of the journey I would write a small dictionary of Tamasheq for my own use and became confident in the basics of their language.

Now as we cowered from the wind Ouankilla read the Sands in the moonlight, a ritual used to predict our fortunes for the next day, his fingers making alien patterns of dots and dashes and circles on the ground. He was rather short with smiling eyes and a jolly nature. It had been a week into the journey before I found out he had a large beard and was completely bald. The Touareg always wear their long headcloths, called a cheche, wrapped around their faces so that only their eyes and nose show. Theirs is the only known culture where the men, not the women, are veiled. At first I found speaking to men whose eyes are only showing a little disconcerting, but in time I had slipped into the practice myself and found comfort in the obscurity it afforded.

Now as we cowered from the wind Ouankilla read the Sands in the moonlight, a ritual used to predict our fortunes for the next day, his fingers making alien patterns of dots and dashes and circles on the ground. He was rather short with smiling eyes and a jolly nature. It had been a week into the journey before I found out he had a large beard and was completely bald. The Touareg always wear their long headcloths, called a cheche, wrapped around their faces so that only their eyes and nose show. Theirs is the only known culture where the men, not the women, are veiled. At first I found speaking to men whose eyes are only showing a little disconcerting, but in time I had slipped into the practice myself and found comfort in the obscurity it afforded.

Whenever I had travelled in the past, I had always been an Englishman abroad. I had worn my own clothes and in bringing a few select luxuries from home had been able to carry my own world with me. But now in order to go some way to being treated equally as those with whom I would be travelling, I would dress as a Touareg. I wanted to be accepted, to some degree, as one of them.

For this reason I dressed as they did in a long blue robe reaching to the ankles and a cheche twisted around my head in their fashion. I wore sandals of camel skin, but more often than not went barefoot. At first I felt very self conscious: my clothes were new and stiff and my cheche bright white compared to their garments, soiled and frayed by the life of a nomad, but soon mine too would become weathered by the desert. I used a stick twined with camel fur for riding, a dagger hung from a belt that I wore tight around my waist with a cartridge belt for ammunition for our .303 rifles. Later in the journey I was given a sword, which to the Touareg is a rite of passage and a symbol of maturity, and is worn around the shoulder.

I ate and drank as they did, drinking the brackish water from wells sometimes 75 metres deep. We would bake hard, unleavened bread from water and semolina, burying the dough in the ashes of a fire to form a makeshift oven. If we chanced on shepherds herding goats in a wadi we could buy one and eat well for a few days. The Touareg eat everything on a goat, from the stomach to the bone marrow, the ears to the lungs. Nothing is wasted. I was often offered the rectum, a delicacy to these people. Water was constantly a problem. The wells were far apart and we carried the water in small goatskins on the backs of the camels. Sometimes one well would serve an area of desert the size of Northern Ireland. In the summer these wells would quickly run dry as the nomads toiled to water hundreds of thirsty camels and I shrank from the thought of what they did for water in these hotter months. Between wells we were rationed to almost two pints of water a day. The thirst was often unbearable and I frequently passed blood in my urine. Thirst would plague my dreams at night and the sloshing of water in the goatskins would taunt me during the day.

I had never ridden a camel for any length of time before coming to the Sahara, but after ten to twelve hours of riding a day I learned quickly. The days began an hour before sunrise, waking to a star strewn night’s sky. The nights were often bitterly cold and we slept on the ground under a blanket, our saddles nearby. Everyday the first task would be to find our camels. Each evening we hobbled their front legs together with rope so they could walk in small stilted steps to find dry grass or acacia trees. Most of the time their tracks on the desert floor gave away their direction, but their incessant wandering only added more miles to the amount we would already have to do as they would often walk five miles in a night.

We crossed the invisible border into northern Mali. Here the Touareg were fighting a bloody war with the government in a bid for equal treatment and for a degree of autonomy. I spent a few days resting, repairing saddles and gathering more Touareg at Aguelhok in the Adrar des Ifoghas, an encampment of tents that covered an area the size of Belgium. I was treated with great hospitality and was dismayed to hear that the week after I had left the settlement had been become a battleground, the army having butchered many of its residents. Unwittingly I had saved the lives of those who had come with me, but many wanted to return to search for their families or bury the dead.

We crossed the invisible border into northern Mali. Here the Touareg were fighting a bloody war with the government in a bid for equal treatment and for a degree of autonomy. I spent a few days resting, repairing saddles and gathering more Touareg at Aguelhok in the Adrar des Ifoghas, an encampment of tents that covered an area the size of Belgium. I was treated with great hospitality and was dismayed to hear that the week after I had left the settlement had been become a battleground, the army having butchered many of its residents. Unwittingly I had saved the lives of those who had come with me, but many wanted to return to search for their families or bury the dead.

I arrived in Timbuktu after two months and found it a disappointment. The beautiful architecture of the houses and mosques was still evident, but the town’s academic allure for which had once been famed was nowhere to be seen. Men hawked trinkets on the street; radios blared by stalls in the market selling goods and clothes made elsewhere and I immediately wanted to return to the quiet safety of the desert, to the Touareg I had been honoured to call my companions on this journey.

Buy a copy of the book Amongst the Touareg here

If you like the pictures, you can also order limited edition prints of the Trans-Sahara expedition and much more here